The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy – part 2: The Warren Commission and Its Critics

Reading time: 15 minutes

Establishment of the Warren Commission

In order to prevent the United States from being regarded as the largest banana republic in the world, Lyndon B. Johnson appointed a commission to investigate the murder of his predecessor. The Commission was chaired by Earl Warren (1891-1974), Chief Justice of the United States. Besides Warren, there were six men on the Commission. Among them were two senators and two members of the House of Representatives (i.e. the leaders of the Republican and Democratic parties in the House). The leader of the Republicans in the House was Gerald Ford (1913-2006), who was to succeed Richard Nixon as President of the United States. Finally, two highly regarded citizens, Allen Dulles and John McCloy, were on the Commission.

Dulles and McCloy were not just ciphers. In his 1957 The Power Elite, American sociologist C. Wright Mills mentioned them as typical representatives of the power elite. Having served as a diplomat for a number of years, Allen Dulles (1893-1974) joined the largest law firm in the United States. He then rejoined the government as its chief spy. For almost ten years, Dulles was head of the CIA. In 1961, after the CIA-planned invasion of Cuba which had fallen through, he was fired by President Kennedy. John McCloy (1895-1989) was Assistant Secretary of War during World War II. He then served as President of the World Bank from 1947 to 1949. From 1949, he was U.S. Military Governor and High Commissioner for Germany. Four years later, he joined the board of directors of one of the largest banks in the United States. (Mills, 233 and 138; Warren Report p.476).

On September 24 1964, the final report of the Warren Commission was presented to President Johnson. He commented that it was a thick volume, and so it was: the book has no less than 888 pages. According to the Report, Lee Harvey Oswald was the (sole) assassin of both President Kennedy and Officer Tippit. Two months later, some of the evidence, including the hearings of almost 500 people, was made public in no fewer than 26 volumes. One might think that this material, totalling almost 20,000 pages, would remove all doubts about what had happened on November 22. However, the opposite was true: an extremely confusing and heated discussion ensued, which continues to this day.

The Warren Commission at Work

Ah, and it had started so well: “This Commission was established on November 29, 1963, because of the right of people all over the world to have full and truthful knowledge of these events. (…) The Report was prepared with the awareness that the Commission has a responsibility to provide the American people with an objective account of the facts relating to the assassination of President Kennedy.” (Warren Report, p.1) The question is whether the Commission has lived up to these expectations.

However, the Warren Commission did not start from scratch, if only because from day one, both the FBI and the Dallas police had stated that Lee Oswald was the murderer. From the start, the Warren Commission was also committed to this view. In December 1963 and January 1964, the investigation was set up and 25 lawyers were appointed to carry out the actual investigation. Some of them had to do this on top of their existing workload. In order to give these lawyers time for preparation, the members of the Commission first started interviewing Marina Oswald (the widow), Marguerita Oswald (the mother) and Robert Oswald (the brother) in February. This resulted in almost 500 pages of interrogation reports. The question arises whether the Commission, having done all this interrogating, was prepared to change course and charge someone else as a murder-suspect.

Gradually, however, the Commission came to realize that the investigation carried out by Dallas police had been lacking in precision. The lack of clarity about what gun was actually found in the School Book Building (Oswald’s or another rifle) may serve as an example of how the Commission handled such matters. Boone and Weitzman, the police officers who had found the rifle, told the Commission that the rifle they had found was German, a Mauser. So it could not have been Oswald’s rifle.

Apparently, the Commission were not sufficiently confident to show the two officers Oswald’s rifle. The Report states that neither Boone nor Weitzman had taken the rifle in their hands, thus suggesting that they never had a good look at it. (Warren Report, p.79) On paper however, both officers had given a clear description of the weapon. Reading the entire Report, one will find (on page 645) Weitzman’s statement that the gun was a Mauser. But, according to the Report, he had only had a glimpse at the gun. There is no mention of the fact that, for a number of years, Weitzman had been employed in a gun shop, so that he knew what he was talking about. Nor does the Report mention the fact that the other officer, Eugene Boone, had also stated that the rifle was a Mauser. In this way, the Commission had gotten rid of the problem. Because the gun (as well as much of the other evidence, for that matter) had not immediately been marked by the finders, a mix-up cannot be ruled out. If the Report had mentioned these facts, its conclusions would have been undermined.

Strangely enough, in the course of the hearings, the chiefs of the Dallas police Department were rather severely dealt with by the Commission, but no criticism of Dallas police is to be found in the Report. If the Report had criticized the police, more of the evidence might have become suspect. Furthermore, the Commission could not find a motive for Oswald to kill Kennedy. Oswald’s acquaintances (as well as his wife Marina) said that he had admired the President and had supported his policies (e.g. on civil rights). So why kill the man?

None of this exonerates Oswald, but it does show that the Warren Commission did not do what it allegedly had set out to do, according to the first page of its Report: to conduct an objective investigation. And because of this selective approach, the Report came in for a lot of criticism.

The question remains why the Warren Commission had had the nerve to treat evidence so cavalierly. As C. Wright Mills pointed out in 1957, the elite (from which the members of the Commission were recruited) were a world apart, with an ideology of its own. Often educated at Ivy League universities and associated with the major corporations of its day, members of the elite regarded their wealth – according to Mills – as well-deserved and therefore felt superior to the rest of the people. In Mill’s view, this ideology extended to the social stratum immediately below the super-rich. After all, the career prospects of the members of this social class depended on the power elite. (Mills, Power Elite, 14, 248 and 348). In the case of the Warren Commission, these were the 25 – mostly young and aspiring – lawyers who had carried out the actual work for the commission.

According to Mills, the members of the elite were not concerned with discovering the truth: they only cared about a well considered public relations policy. Reasonable argumentation was not considered of prime importance, but manipulation of facts was, as well as making decisions based on their power. All in all, this made democratic checks impossible. (Mills, 286 and 355). In this way, Mills gave – avant la date – a correct description of the way in which the Warren Commission was to conduct its investigation.

Protected Against Criticism

The Commission had given due attention to the purpose of the Report. In at least three ways, the Warren Commission tried to ensure that its conclusion would be accepted as the truth and nothing but the truth. The first chapter of the Report provides a 25-page summary of the research, useful for journalists who, of course, did not have the time to dig through the entire book. In the summary, all wrinkles were ironed out. Critics who reviewed all of the 26 volumes of hearings and documents, found many inconsistencies between the evidence and the polished rendering thereof in the Warren Report. But by offering a convenient summary, the Commission had expertly misled the journalists.

Secondly, the Commission attempted to ensure that criticism would be silenced. To this end, the Commission wrote a separate chapter in which it briefly refuted all matters about which some of the media had expressed their doubts. This was not always very convincing, as was already apparent in the discussion of the rumor that the gun that had been found was not Oswald’s.

Thirdly, after the publication of the Warren Report, the Commission was immediately dissolved: “the debate is now closed”, was the Commission’s message. It was not going to participate in the debate that subsequently erupted. By writing the Report, the authors had achieved their short term goal: the culprit had been officially identified. The convenient summary had been instrumental in convincing the media.

Conspiracy Theories

Conspiracy theories have a bad reputation. In his introduction to history, Robert Williams discusses a number of examples of what he calls anti-history. His first example concerns the denial of the Holocaust. But he goes on by mentioning as a second example of anti-history: “A great conspiracy was responsible for the death of President John F. Kennedy.” Williams: “These are false claims. There is no evidence for them.” (Toolbox, p.32) Any sane person will find the denial of the Holocaust a bizarre idea indeed. But does that mean that the Warren Report is a sacred book and therefore beyond criticism?

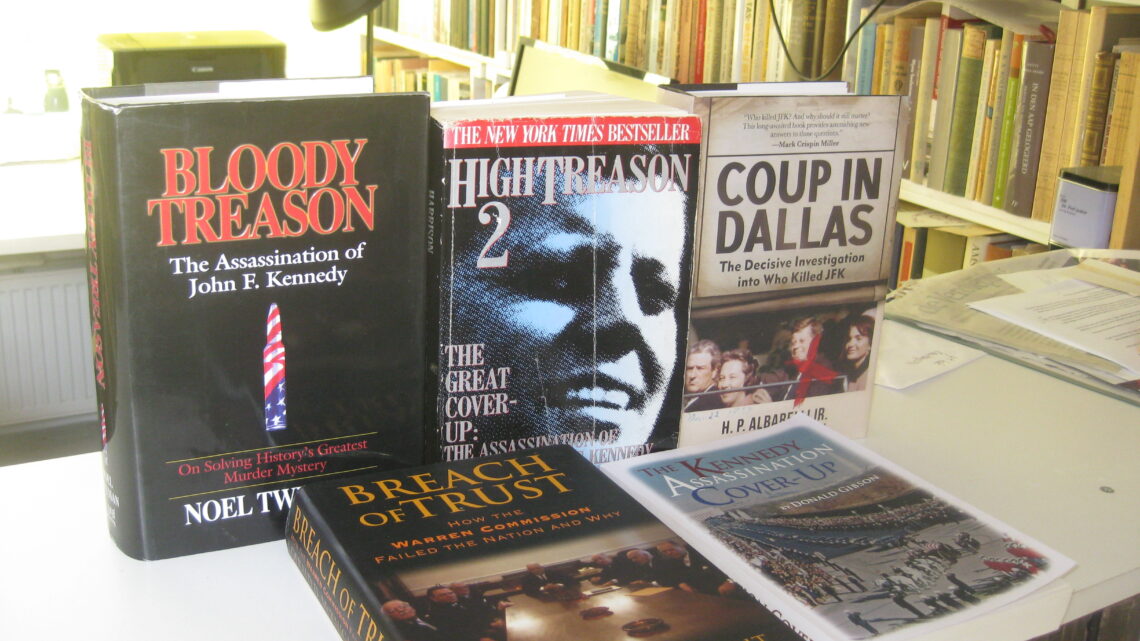

Critics argue that the Commission had damaged people’s trust in their government and, as a result, had created the most notorious conspiracy theory of all conspiracy theories. Soon after the publication of the Warren Report, it came in for a lot of criticism. More than one thousand books and countless articles have since been published on the best documented murder case in history. Most of these publications assume that there was a conspiracy to eliminate President Kennedy. The critics of the Warren Commission often blame the Commission for more than having made mistakes. According to many critics, the Commission deliberately distorted or ignored facts that did not fit its theory, possibly in order to protect the real perpetrators of the assassination.

The conspiracies outlined in the thousand books, often differ from one another. They frequently focus on the groups of people who had a motive to kill President Kennedy. Let us have a look at a number of those theories.

In the first place, organized crime had a clear motive. Robert Kennedy, the President’s brother and U.S. Attorney General, had started a campaign to wipe out organized crime. The idea was that if the President was assassinated, his brother would be gotten rid of as well.

Secondly, the FBI is often mentioned as being involved in the assassination. Its director, Edgar J. Hoover, had come to regard the FBI as his own private empire. But when Robert Kennedy became Attorney General and took matters in his own hands, Hoover became subordinate to his new boss. Again, the theory was that if the President disappeared, his brother would also be removed from office. Critics point out that from the start, the FBI saw Oswald as the only culprit and had therefore ignored other leads. This too made the FBI suspect.

The third suspect is another powerful federal organisation: the CIA. According to some critics, the CIA had become a state within a state and had been afraid that President Kennedy would curtail its power. In 1961, Kennedy had already fired its director, Allen Dulles. In some countries, the CIA had tried to overthrow the ruling government. After 1963, it would continue to do so. In 1973, for example, the left-wing president of Chile, Salvador Allende, had been deposed with the help of the CIA, after which a military dictatorship was established. That is why some of the critics put the CIA in the dock.

Finally, there is the problem of Cuba, where Fidel Castro came to power in 1959. Many supporters of the deposed and corrupt dictator Batista had fled to Florida and Louisiana. There, sometimes with the help of the CIA, these refugees set up camps to train volunteers for another incursion into their old homeland. After the failed invasion and the Cuba crisis of 1962, President Kennedy was reluctant to make another attempt to overthrow Castro’s regime, and this is supposed to have given the Cuban exiles a motive to assassinate Kennedy.

It is clear that all these theories contradict each other, and the role attributed to Oswald varies from theory to theory. Had Oswald really been a left-winger or had he, after all, been an informant of the FBI, as was rumoured at the time? Up to a point, it is therefore understandable that Williams discards all these theories.

Are the Real Culprits Still to be Found?

As Josiah Thompson stated in 1967, it is very likely that there were at least two shooters at Dealey Plaza. One of them shot from the School Book Building or from a nearby tall building, and the second shooter fired from a knoll adjacent to Elm Street, where Kennedy’s motorcade drove past. This knoll would later be called ‘the ‘grassy knoll’, but this term is nowhere to be found in the Warren Report. And that is strange: the ‘grassy knoll’ was the exact spot almost immediately identified by police officers and civilians alike, as the location of the shooter. Last year, Thompson repeated his research using new data. He came to a similar conclusion, but wisely made no statement about who the shooters could have been. Nor does he answer the question whether Oswald was one of them. (Thompson, Six seconds in Dallas and Last Second in Dallas).

McKnight also concludes that there was a conspiracy. But he argues that so far no smoking gun has been discovered in the documents released by the U.S. government. He says it is unlikely that such a thing will ever be found, because the organizations who should have investigated the murder thoroughly (Dallas Police, the Warren Commission, the FBI and the CIA) had failed to do so. (McKnight, Breach of Trust, 354).

So far, Victor Bugliosi wrote the thickest book about the Kennedy assassination. He is not a fan of conspiracy theories; on the contrary: according to him Lee Harvey Oswald was, without a doubt, the murderer of President Kennedy. But he also makes it clear that if there had been a conspiracy, the assassins would have ensured that nothing was put on paper. (Bugliosi, Reclaiming History, endnotes p. 676).

Conclusion

Most conspiracy theories contradict each other as to whether Oswald was one of the gunmen. The next few blogs in this series will take a detailed look at the way the Warren Commission operated. Then, we may possibly be able to answer the question whether Oswald was guilty of the assassination of President Kennedy.

Sources

C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (New York 1957); Warren Report (Washington DC 1964); Hearings Before the President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy (Washington DC 1964, 26 volumes); Josiah Thompson, Six seconds in Dallas (New York 1967); Robert C. Williams, The Historian’s Toolbox: A Student’s Guide to the Theory and Craft of History (New York 2003); McKnight, Breach of Trust (Kansas City 2005); Victor Bugliosi, Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy (New York 2007); Josiah Thompson, Last Second in Dallas (Kansas City 2021).

Plan for the next blogs:

Part 3: How (not) to Investigate a Crime Scene

Part 4: Oswald on the Stairs – the Time-Tests Made by the Warren Commission

Part 5: The Paper Bag or the Way in which the Warren Commission Handled Evidence

Part 6: Lineups or the Way in which the Warren Commission Handled Evidence

Part 7: The Interrogation of Lee Harvey Oswald

Translated by Ite Wierenga