Loving Parents? Part 1: Cotton Mather (1662-1728)

Reading time: 9 minutes

Around 1575, the French philosopher Montaigne remarked that he had lost two or three children as babies “if not without grief, yet without much repining.” He has often been reproached for using these words: how could anyone show so much indifference about the death of his children that he did not even know how many of them had died? However, historians such as Ariès saw this as evidence for their claim that in the 16th and 17th centuries the death of very young children was not the sort of calamity for parents it would now be. In their own families people had become accustomed to deaths of their baby-brothers and -sisters. One in every four children died before their first birthday. According to Ariès, this meant that parents became less attached to their young children. Consequently they accepted child death more readily and their grief was less intense.

The focus of this series of short essays is the question whether parents in the 17th century parents felt greatly attached to their very young children and whether they felt great grief when their children died at so young an age. Now, a number of extensive 17th century diaries have been preserved, and they may give us some clues for trying to find some tentative answers.

Boston was the capital of the British colony of Massachusetts. Until 1776 (when the Americans rebelled against Great-Britain), the British government appointed a governor for each state. . Bron: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

Cotton Mather (1662–1728)

The first diarist we examine is Cotton Mather, who was a Puritan clergyman in Boston, a town that had at that time a population of about 10,000. In 1702, six months after the death of his first wife Abigail, Cotton married again. He also survived his second wife: in November 1713, she died from measles, together with her new born twins and a two year old daughter. Only two of his 15 children survived him. Admittedly, Cotton Mather was not your average person. His diaries are mainly about himself, stressing the fact that – in his own words – he worked on earth as an instrument of God.

He believed in the existence of witches and he claimed he was in direct contact with God. Cotton Mather may have been a superstitious, short-sighted, and vain mystic (at least that’s the way the editor of his diary characterized him in 1911), he was fully devoted to his job as a minister. For example, during a smallpox epidemic, he visited the homes of the sick to give them support, risking getting infected himself. And during severe winters, he handed out money from his own pocket to the poor and successfully encouraged others to do the same.

During the day, he spent a lot of time preparing his sermons (which he often published in print), visiting parishioners and the sick. He spent much time in prayer, often for hours on end, mostly alone but also regularly together with his entire family. Cotton wrote no less than 450 books and pamphlets. This probably explains the notice on the door of his office, intended for visitors: Be Brief.

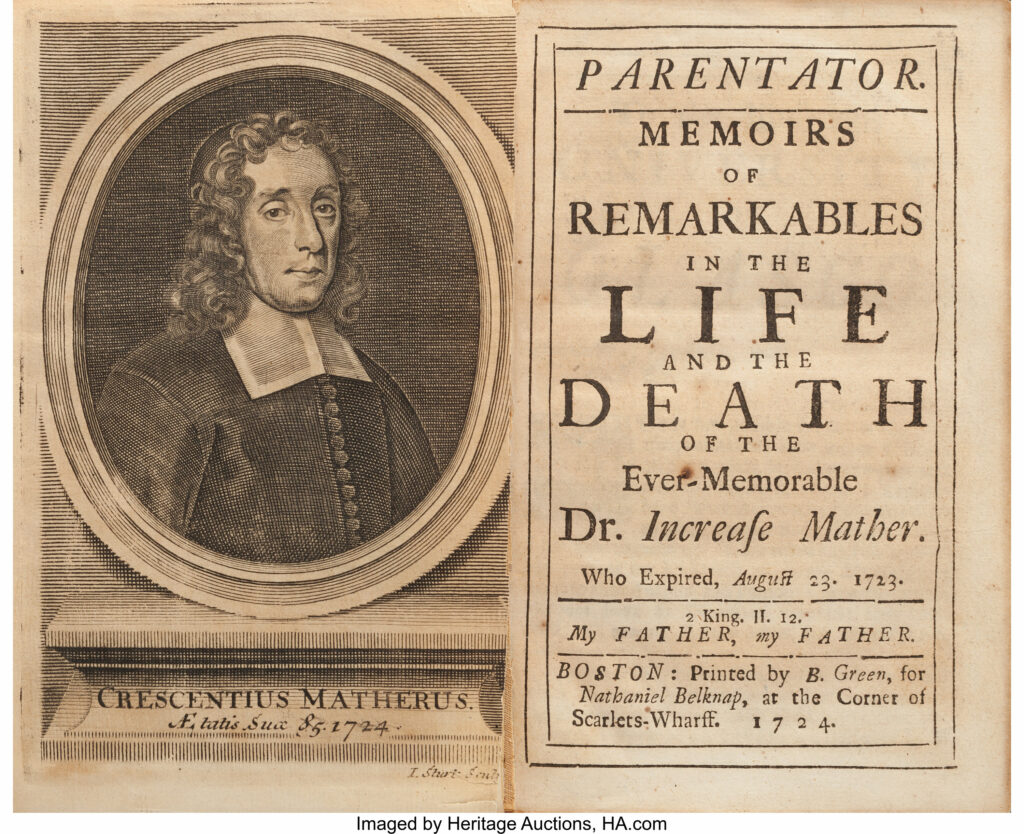

[Image reprinted by permission of Heritage Auctions, Dallas TX]

His Children: Joseph, Mary, Katy, Mehetabel and Nibby.

Cotton was devoted to his work, but just as much to his children. In late March 1693, at the birth of Joseph (who died after three days), Cotton wrote: “We used all the methods that could be devised for its ease, but nothing we did could save the child from death.” In October of the same year, his 2-year-old daughter Mary died. Cotton wrote that having prayed for hours at a time, he had received God’s assurance that all his children would go to heaven. That was a great comfort to him.

By January 1694, Cotton Mather had only one child left, born in September 1689. In that year this girl, Catherine (pet name: Katy) fell seriously ill, and there was no hope that she would live. “In my distress when I saw the Lord thus quenching the Coal that was left unto me and rending out of my bosom one that had lived so long with me, as to steal a Room there.” Fortunately, Katy recovered. But she was not to survive her father: she died in 1718.

In February 1696 his one-year-old daughter Mehetabel died: “Alas the child was overlaid by the nurse.” In order to keep very young children warm in the poorly heated houses in the very cold winters (and in the absence of hot water bottles) parents or the nanny used to take the children to bed with them. It was not seldom that in their sleep adults smothered a child. This is what happened in the Mather family.

Mather hoped God would help him “to a patient and cheerful submission under this calamity; though I sensibly found, an assault of temptation from Satan, accompanying of it.” Cotton saw his grief over the death of his child as a temptation from the devil. Cotton regularly prayed for his children, including the deceased ones, like in February 1696 after the death of Mehetabel: ”Four of mine are now flown thither before me.” Whenever one of his children was sick, Cotton would pray and blame his own sins for the illnesses of his children: God punished him for his sins by taking his children away.

It is evident that Cotton was not indifferent to his children. On the contrary, he was very apprehensive when something was amiss. Not only did babies get sick, accidents were also common occurrences. In February 1697 his two-year-old daughter Abigail (pet name: Nibby) fell into the fireplace, but she sustained no injuries. In October 1700, Nibby’s hair caught fire when she walked too close to a candle. She couldn’t cry for fear, but a passer-by saw the blaze, came in and succeeded in putting out the fire. The attention and love Cotton had for his children is evident from the account (half a page long) he gave of this incident. Cotton saw it as a disposition from God that someone passed the house at the right time. However, Cotton was to witness Nibby’s death in 1721.

His Children: Nanny

In some cases, when a child had been given up by the doctor, as in the case of Nanny for instance (pet name for Hannah, born in 1697) things took a turn for the better. A few days later, Nanny was hopping around the room again. According to Cotton, this was the result of his many prayers for her. Hence his exclamation: “Thank God!” In March 1701 Nanny fell ill again, and this time too it was thought that death was near. Cotton prayed and prayed and he wrote that he had received assurances from God that the child was to live. A month later, the child was well again. Cotton: “Faith is no fancy!”

In February 1705 Nanny was struck again by high fevers; but again, according to Cotton, she recovered thanks to his prayers. But in May of the same year things went wrong again: she had high fevers and now things looked very grim. The Puritan Cotton Mather saw these intense fever attacks as a test from God: “God awakens me by her sufferings, to mourn for my sins against him, and to think what special duties He calls me to.” To every one’s surprise she recovered once again. She was the only daughter to survive him.

A Loving Father

Despite his very stern and strict faith, Cotton’s anxiety about his children’s lives is instantly recognizable from his pages. The affection he had for his children is also evident from the pet names he gave them: Nibby for Abigail, Katy for Catherine and Nanny for Hannah.

A page from Cotton Mather’s diary. At the end of the 17th century, one in every five households in Boston had slaves. Both Cotton Mather and his father owned Native American slaves. Cotton’s slave was captured by the French, with whom the English government was at war most of the time. After much ado Cotton’s slave was eventually returned by an English warship. Unlike his friend Samuel Sewall, Cotton had no qualms about the phenomenon of slavery.

His concern for his children is also evident in Some special points, relating to the education of my children. In this document he wrote that he told them stories from the Bible at the dinner table every day and taught them to say their daily prayers. When schooling fell short, his children received extra lessons from him and his father. Of course, Cotton was always in charge. He also wrote that he was averse to corporal punishment, except on rare occasions. He thought it was better for them “to be chased for a while out of my presence.” Centuries before the term was invented, Cotton already applied the concept of ‘time-out’.

Finally, the attention and love that Cotton had for his children appears again in an incident in January 1707. Cotton’s little son Increase (pet name: Creasy, born in 1699) went to his grandfather’s every week and was then tutored for a while. But on this occasion he had to run an errand for his father first. As a result he arrived late at Grandpa’s. Grandpa was angry, and refused to tutor him and sent his grandson back home. Creasy arrived at home in tears. Cotton sent a message to his father saying that it was his own fault and not his son’s. He asked his father to make it up to Creasy, which Grandpa did.

Comforted by Faith?

Cotton Mather was not dulled by the death of so many of his children. As we saw, there were misery and grief every time. What we do observe is that he was even more saddened by the death of his older children than he was when newly-born babies died. He says this in so many words when 4-year-old Katy is seriously ill. She had been with him for so long that she had occupied a permanent place in his heart.

In one of his pamphlets Cotton wrote about the idea of original sin. According to his strict Calvinist and Puritan views, children were born as sinful creatures: “Are they young? Yet the devil has been with them already.” However, this view did not affect the way he treated his children. But when a child died, this damning idea caused him great anxiety: was heaven their destination? The Puritan God he imagined was not such a loving father as Cotton himself had been. But his anxiety is yet another proof of the love Cotton felt for his children.

Sources: Diary of Cotton Mather 1681-1708 (Boston 1911); Elizabeth Bancroft Schlesinger, “Cotton Mather and His Children”, The William en Mary Quaterly, April 1953 (Vol. 10), p. 181-189 (downloaded from: www.jstor.org); E. Jennifer Monaghan, “Family Literacy in Early 18th-Century Boston: Cotton Mather and His Children”, Reading Research Quaterly Autumn 1991 (Vol. 26), p. 342-370 (downloaded from: www.jstor.org); Sarah Bakewell, How to Live or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (London 2010).

Translated by Ite Wierenga