The Powerless Church in the Netherlands in the 17th and 18th Centuries

Reading time: 9 minutes

How could a potentially revolutionary Christianity (“love your neighbor as yourself”) become a travesty of itself?

Amsterdam in 1740: the Chilliness of a Christian Society

The winter of 1740 was very harsh, it was freezing cold. As a result, there was also a great shortage of drinking-water. At the beginning of February, an older couple, living in a dilapidated house in the Franse Pad, had gone to bed, but because of the cold the woman couldn’t sleep. They had no money to buy fuel. After a while, when she wanted to talk to her husband, it turned out that he had died of the cold. The woman got up, called some neighbors to lay out her husband’s body, and then went back to bed. Next morning when the cart from the hospital arrived for her husband’s burial (they were poor), it appeared that the woman had also died. In the next few months of the winter more people died from the cold.

Drawing from around 1820 by J.H. Knoop (source: Beeldbank Stadsarchief Amsterdam – Amsterdam City Archives Image Bank)

Two weeks before this, some sailors (who had already signed on) had asked the directors (the so-called “bewindvoerders“) of the Amsterdam branch of the Dutch East-India Company (V.O.C.) to give them board and lodging so that they would be protected from the cold. Due to the severe frost, they could not (or were not allowed to) get on board. The directors however, refused to help them. When the directors left the building of the V.O.C. after a while, the sailors were still there and began throwing litter at the respectable gentlemen. Several of the sailors got run in and were publicly flogged a few days later. After the flogging one of them was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment.

Three years later, one of those directors of the Amsterdam branch of the VOC died: the immensely rich former mayor Lieve Geelvinck (1676-1743). When he felt he was going to die, Geelvinck sent for a minister. They intended to pray together and with great difficulty Geelvinck got up from his chair in order to kneel down and join the minister. The chergyman told him that God would certainly appreciate this intention, but that he had better remain seated because he was too weak to kneel down. To which the former mayor replied: “The little energy God still grants me, I will spend to serve him” and he also lay down on his knees to pray.

Are We in a Position to Pass Judgement on the Actions of People in the Past?

We know about the events just described because they were covered by Jacob Bicker Raije (1703-1777) in a diary he kept for 40 years: from 1732 to 1772. At the time, Amsterdam was the third largest city in Western Europe, after London and Paris, with over 200,000 inhabitants. There was ample material for him to report in his diary. Jacob was fascinated by the scenes he experienced or had heard about. In his diary the riches and extravagance of the wealthy inhabitants of the city contrast sharply with the misery in which large parts of the population had to live.

Painting by C. Springer, 1875.

It is often alleged that we should not judge, let alone condemn, behavior in the past on the basis of our current values. This is regarded as unhistorical and unjustified. Should we – just like Jacob – find it touching that Geelvinck tried to pray to God with the little energy he had still left? Or should we label Geelvinck as a hypocrite, because he felt this need for prayer in faith, but had refused to put that faith into practice: after all, despite his enormous wealth, he had left the sailors in the cold, both literally and figuratively.

People in the prosperous ‘christian’ Dutch Republic were left to die of the cold and could be locked up when they resisted the wealthy rulers. The Dutch historian Johan Huizinga once said that historical periods are never homogenous: in the past too, opinions differed greatly on many matters. Before Jacob started writing his diary, several Dutch ministers had already strongly protested against the way of life of the rich. We’ll discuss the ideas of two ministers: Saldenus and Lodenstein.

“Gold is Their God”

In 1667 Saldenus (1627-1694) sharply criticized the way of life of the wealthy of his day. In a booklet dealing with the subject of memento mori. Saldenus complained about the decline of charity. “Where are now the gifts to the poor instead of gifts to those who do not need anything? Kindness to the poor is a loan to the Lord. Take this to heart, you merciless rich people, who will not act when the poor and needy starve to death, or who give so little to the poor in your wills.”

Yes, there were people who did think of death, said Saldenus. But they were concerned with ordering beautiful tombstones and obtaining offices and high positions for their children. However, Saldenus also gave fair warning: it is also important to enjoy life on earth and not give away all one’s possessions. This was probably a little superfluous, but it does indicate that even in those days there were apparently people who really tried to act upon the Gospel.

More incisively than Saldenus, Lodenstein (1620-1677) expressed similar criticisms. He belonged to the small minority of Pietists who stressed the importance of the inner life of faith and the practice of charity. Lodenstein was unmarried, financially independent and lived in a beautiful mansion in the city of Utrecht. He gave freely to the poor, and led an ascetic life. He got up between 3 and 4 in the morning: the man needed little sleep.

Drawing in: M.J.A. de Vrijer, Lodenstein. (Baarn ca. 1935)

Lodenstein condemned the “oppression of the common man”, but also the swearing and frequent visits to bars and gambling-dens. But Lodenstein’s criticisms especially addressed the rich of his day who called themselves Christians, but did not live up to that claim: in his view they were only ‘nominal Christians’: “But look at those people craving for the dross of the earth! Gold is their God. They scrape money together.” According to Lodenstein these so-called Christians enjoyed their wealth so much that they forgot that their wealth should also benefit the poor.

Lodenstein pointed at the first Christian community in Jerusalem, where all goods were considered common property. According to Lodenstein that meant much more than just charity. That way of life should serve as an example for the Christians in his day, but the vast majority of the rich did not think that way: “But look how little actually comes of it.” However, the poor were not meant to forcibly claim the property of the rich, for the rich had been appointed by God as stewards. In this way, Lodenstein had manoeuvred himself into a stalemate: he gave no leeway for the poor, only warnings for the rich.

How Could a Potentially Revolutionary Christianity Become a Parody of Itself?

Lodenstein’s and Saldenus’ admonitions had very little effect. The fact that Lodenstein lived in a beautiful mansion must have made his warnings for the rich somewhat unconvincing. And in the case of Saldenus, the subject matter of the book in which he criticized the rich must also have diminished its effectiveness. This book was about how to deal with one’s impending death, how to prepare for the hereafter. In those days too that was not a favourite topic for most people. Basically, Saldenus discussed two taboos: the dangers of being a rich man and of becoming a dead one. Therefore, his book may not have been widely read, despite its many reprints, well into the 20th century.

But there is a more important reason why these ministers could not change the church, a reason Lodenstein had mentioned too: “The worldly people have the upper hand. If the pious were to prevail, Jesus would be King. The Church is ruled by the spirit of the world. Everyone desires to be most important.” The church of those days was subordinated to the government, which could fire ministers, so that any fundamental criticism supposing ministers felt the need to utter at all could never be very successful.

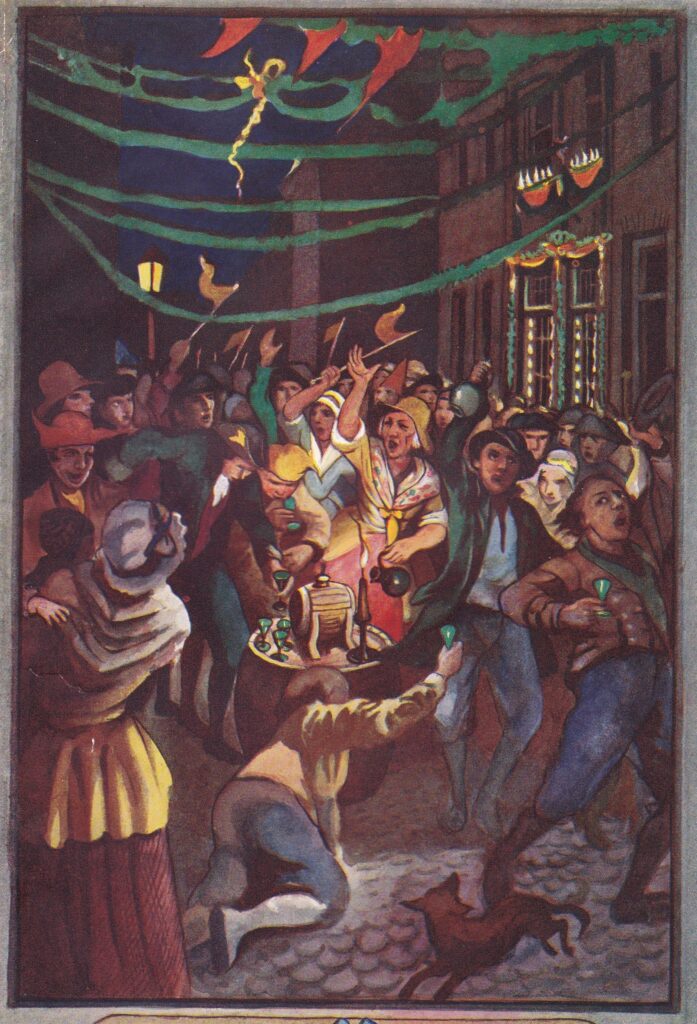

Watercolor by G.D. Hoogendoorn from: A.A. Van Schelven, Van hoepelrok tot pruikentooi (Nijkerk ca. 1935)

Huizinga said that historical periods are never homogeneous. There has always existed an undercurrent in the Christian church(es) that strove to put Christian doctrine into practice, but it was no match for the mainstream church, ruled by the elite. It would seem as if most ministers just gave up (possibly sometimes out of sheer necessity) and no longer focused on the root of all sin: idolizing wealth. Instead, they protested against relatively petty sins, such as frequenting pubs, fairs, and gambling-dens. These were customs that were seen by the ministers as folk-sins, but which were partly the result of the unjust organization of society. They served as an outlet for the vast majority of the population which could only survive by toiling very hard. That way they had their share of fun too. The most serious sin was, admittedly, not addressed, but even the rich knew that what they were doing was wrong, they were no prisoners of their times, or of their culture. Instead, they were – then as now – prisoners of Mammon, the idol of money.

Translated by Ite Wierenga